When students struggle with speeches, presentations, or pitches, it often stems not from research issues, lack of knowledge, or insufficient content. Frequently the opposite is true, and I hear that time honored refrain, “I don’t know where to go with this.” Teaching speakers to research, link information together, and produce slides is the easy part of coaching and training. Teaching effective construction and delivery is the true challenge. Why? Because the former is about how people work while the latter is about how they think. Herein lies a fundamental challenge of public speaking: making it flow.

What is flow? From a technical standpoint, it is a speech’s progression from point to point building toward the overall thesis. It is both the structure and execution of a speech, the arrangement of elements and transitions centered a central idea. In short, a speech’s flow is its story. When dealing with the struggling students mentioned above, that’s one of the first things I say – “Tell me a story.” There is an elementary difference between “deliver a speech” and “tell a story.” Our mindset, the pressures we put on ourselves, and the lens through which we view the work fundamentally shift.

If I’m giving a speech, I’m worried about technical accuracy, information, making mistakes, ensuring my slides are right, worrying over the audience’s reaction, and so on. If I’m telling a story, I concern myself chiefly with getting to the point. Consider the one coworker whose stories you dread. They ramble, offering disjointed, pointless anecdotes that ultimately fail to deliver on what promised to be an enjoyable narrative. Then think of your one friend who could tell a story about making a sandwich, and somehow you end up hanging on every word. While there are numerous factors influencing both scenarios, flow is a huge part of each speaker’s impact.

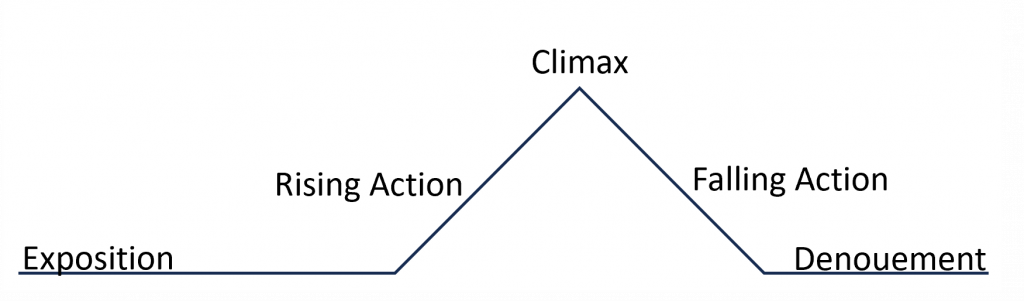

Take a look at the below graphic:

This diagram, commonly taught in composition classes, details the element of narrative structure. Exposition is the “once upon a time” scene setter. Rising Action recounts the characters’ journey toward their confrontation with the final boss at the climax, the villain’s defeat. Falling Action follows our characters back home, and denouement gives us closure – maybe even a thoughtful life lesson.

Speeches can and arguably should follow the exact same structure. Even the most mundane informative speech can hook and hold an audience from beginning to end if it flows well. What’s more, effective flow allows you to say more with less. Consider that the Gettysburg Address is only 10 sentences long and can be delivered in about two minutes. Over 150 years later, we are still talking about a single, short speech above all of Lincoln’s other public addresses – and over the two hour speech given by someone else just before Lincoln spoke. Can you even name him?

There is no universal guide to flow. Like visual effects in movies, you only notice it when it’s done badly. There is, however, as close to a universal structure for speeches that will facilitate good flow. It largely mimics the narrative structure above, but with different terms given the subject matter:

- Hook/attention getter

- Overview

- Main point(s) (from least to most impactful)

- Talking point(s) (from least to most impactful)

- Conclusion

- Call to action

The hook and overview are your “once upon a time” scene setter, getting the audience’s attention and letting them know what you’re planning to tell them. Your main points progress in impact, climaxing with the most impactful statement. Falling action comes in the form of a conclusion, and you provide a denouement for your audience via call to action.

I often hear objections about putting these elements in more pedestrian presentations like an informative speech, and I always contend that they are more important in such circumstances because they are the tools by which you gain audience buy-in. Say your presentation is about light bulbs. Which intro would reel you in more?

A: Good morning. My name is Red E. Speaker, and today I’m going to talk about the history of light bulbs.

B: What would you do if you built a product so long-lasting, you couldn’t sell enough of them to stay in business? I’m Red E. Speaker, and I’m going to talk about conspiracy, cartels, and collusion through the history of the humble light bulb.

In just a few seconds more than version A, version B promises an intriguing story, tantalizing facts, and a potentially enjoyable narrative – and it’s still just an informative speech about light bulbs.

What about the other end of the speech? How do you have a call to action for an informative speech about light bulbs? I think confusion around call to action stems from its general association with persuasive speaking, e.g., a sales pitch where the call to action is for the audience to buy the product. If there is no sales component, however, a call to action can invite the audience to apply the knowledge presented. For those curious, there was an actual light bulb cartel in the early 20th century where several manufacturers colluded to limit lightbulb lifespans, ensuring planned obsolescence.

Let’s look at two possible conclusions and call to actions.

A: This concludes my presentation on the history of the light bulb. I hope you learned something today that you didn’t previously know about light bulbs.

B: In conclusion, we see the unsettling attraction of profits over product and customer well-being. Consider for yourself – are there people in your life artificially limiting you, working to limit your utility because they fear your potential?

Version B might seem a bit dramatic, but in a way that’s the point. Consider the last movie you saw that had tremendous potential in premise but fell flat in execution. In the same way, an uninspired topic can birth an inspired speech. No matter how dull the subject matter might seem, a speech or presentation on any topic, given the right flow, can transform from a humdrum work or school assignment into an engaging narrative.

Next time you find yourself struggling to structure your presentation for work or school, take a step back from the material and say to yourself, “Tell me a story.” You may be surprised at how your approach changes and how much more easily the order and flow come to mind.